Location: Milan, Italy

Architect: Piero Portaluppi

Completed: 1932-35

If you know of Piero Portaluppi's work you are likely to have a connection to Milan as there's nothing published on the architect in English. I was introduced to his work at Villa Necchi by a Milanese friend and architect, Massimo Curzi, a few years ago. I remember it felt like an ancient house in a modern idiom. I've been back four time since; there's a kind of magic there and I find it very inspiring.

Portaluppi is not a pivotal historical architect like his near contemporary Giò Ponti - Portaluppi's work is comparatively a much more difficult prospect. Villa Necchi is quite testing as a building in parts, but I think it has something very special about it.

There's a tension in the house between architectures of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. Is it a proto-modernist villa or is it a nineteenth-century villa brought into the twentieth century? Is it art deco?

The term eclectic is sometimes used pejoratively but I really appreciate the things that hover between. It represents the promise of and the antidote to the modern project - sufficiently modern to not be a stifling nineteenth-century pastiche, but not throwing the baby out with the bathwater and becoming a mechanistic intellectual exercise in newness and eradicating distinctions.

Villa Necchi is in a very well-to-do part of Milan. It was commissioned by a wealthy family who made their money from sewing machines. I appreciate patronage where the client and architect clearly went into great detail about every aspect of the house. It's rare.

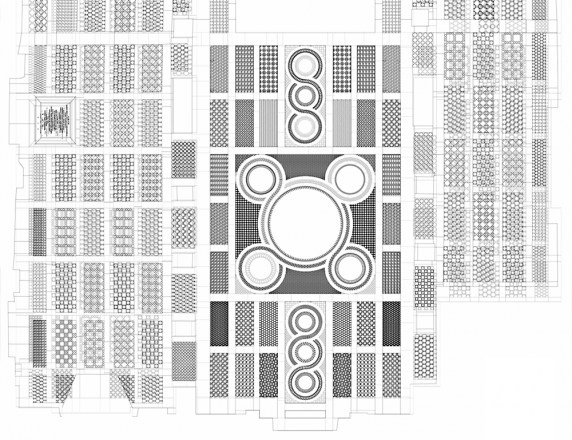

Formally, the house is simple, with no gymnastics. Rather, the architecture is fascinating for how it sets up nuanced relationships between different uses, between different times of the day, and between inside and outside. Everything is choreographed to have a legible hierarchy. There's a pleasure imagined in every corner that is palpable. It would be lovely to live there, for a while.

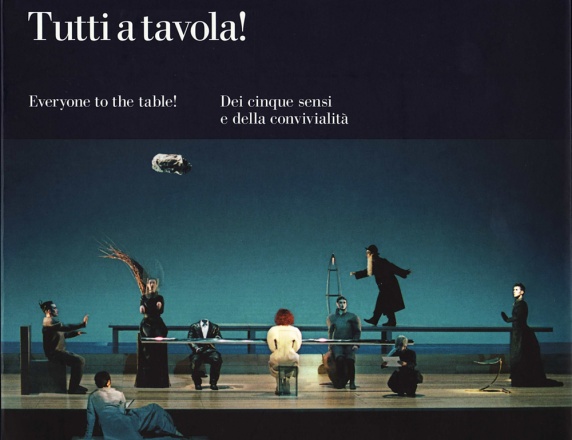

Inside, there's a grand enfilade of rooms but within these are separate datums and the spaces of the rooms are often much larger than the social settings themselves which sit happily within them. The lessons for public and semi-public spaces at different scale are evident. There's both intimacy and space for conviviality. It's just waiting for people to come in and have a great evening.

The entrances are significant because being enfilade rooms, there are no corridors and you have to pass through every room to get through to the next. All the doorways have sliding screens that disappear into the walls so that it can be read either as one space or as separate rooms.

The garden room is one of my favourite rooms in the world. It is like a dream space. There are these very big expanses of window on two sides with a sliver of ferns between two planes of glass. It's like the garden is stored in the walls. If you sit down on the sofas, you can't see the ground outside so it feels like you're up in the trees. There's also a delicious Portaluppi-designed lapis lazuli table and a marble floor that appears woven like tartan. But it all reads as a delightful whole.

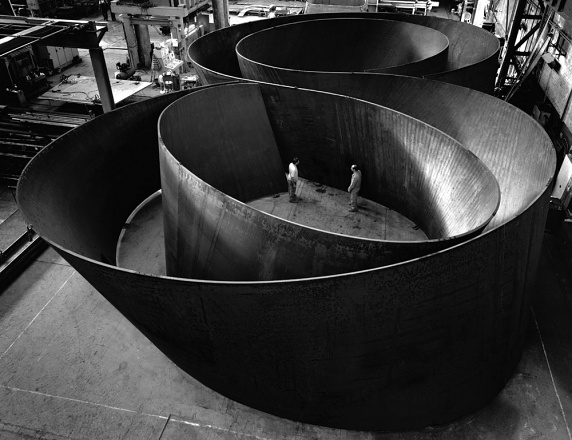

In the library, the ceiling is quite brilliant. It is an asymmetrical diamond pattern with a theme of weaving that you can also see in the marble floors. It creates a sense of tension across the room. This is integral to one's perception of the form and weight and structure overhead, which seems as light as fabric, as though stretched. Portaluppi designed amazing details and the level of craftsmanship right down to the hinges is extraordinary. Although it's very well made, it does not feel gluttonous. Here, it feels like a background setting to heighten the comfort and pleasure of those using it.

There's the incredible, veneered staircase opposite the entrance; the mirrored, diamond-patterned screens to the dining room; the goat leather panelling on the dining room walls, and the personalised Portaluppi-designed crockery, for example.

The dining room is a place where the mix of architects involved - Portaluppi and Tomaso Buzzi, who worked on the house after the Second World War - is really problematic and it lapses into kitsch.

Upstairs, I love the star window - from the outside you wonder which room it's in and then you go upstairs and find he's put it in the toilet. It's very playful.

In the work we do, I often try to find extremes - something very open yet very intimate and comfortable. A trick is to create smaller spaces through openings and niches like at Villa Necchi, where the architecture invites movement and change.

Portaluppi was influenced by different things at different periods in his life. I try to look at different periods in his life. I try to look at different architectures in history and how these can be assimilated into a new language. Villa Necchi has also taught me how the divisions between rooms are important, and how the architecture is inflected to invite certain kinds of uses, whether it's a huge window overlooking the garden, or the lobby to a dining room where you gather before the doors are opened. Despite the materials and the geometries, Villa Necchi forms a background, a setting for its inhabitants' use. It's clearly not saying that a background has to be neutral and bland. Instead it is rich and retains a kind of informality that allows you to choose to occupy it rather than feel that you're being put on show.

There are a few things my practice has referenced directly from Portaluppi's work. Our interior for the Carrer Avinyó apartment in Barcelona followed a Portaluppi pattern but in different colours and framed glass spaces that are like internal winter gardens. Our house in Norfolk for Stuart Shave has a sequence of rooms partly informed by the Villa Necchi.

The Villa Necchi is not perfect, or rather it is not trying to be perfect Instead, there are tensions in the architecture that make it challenging and invigorating. That was perhaps a source of pleasure for Portaluppi when designing the house. And so it is for me.