Published in Building Design, October 2008

Richard Serra’s show at Gagosian Gallery is his first in Britain since Weight & Measure at the Tate in 1992, and his first solo gallery show in the UK. This is surprising for such a celebrated sculptor until you consider the nature of the work.

As Serra pointed out, he does not make merchandise. His trademark enormous plate steel forms require articulated lorries and road closures to install, and do not come in miniatures or editions. Specifically made for the context in which they are first displayed, ideally once in place, they stay.

My interest in Serra’s work was sparked by a show of four torqued ellipses at Dia Chelsea, New York, in 1997. This was the first time Serra had exhibited such forms, since a staple of his work. I had been aware of his landscape pieces and flat-plate gallery installations, but the effect of the ellipses in the tight confines of the Dia gallery was intoxicating by comparison, no less so for Serra. “That was an enormous sea change for me, “ he says, “because up to that point the audience was very, very resistant — but people were very receptive to those pieces. When I came down at the weekend, people were sitting inside them, it was hard to understand.”

During my interview with Serra, he acknowledged the torqued ellipses were born of the desire to make pieces you could walk into. But the genesis of the forms came from an unexpected source, as he explained. On entering Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1638-39) on a visit to Rome in the early 1990s, Serra had the initial impression that the oval plan and ceiling were not one above the other but somehow at an angle. This misunderstanding led to investigations back in the studio involving bicycle wheels, string and sheets of lead, into what volumes this arrangement might reveal.

From the outset, it appears Serra was keen to avoid architectural comparisons with his work. He dismissed conical forms, where the radius reduces as the form rises, and twisting forms, where the oval rotates. The choice of steel rather than concrete, which was briefly considered, was to help develop a logic that was particular to the work and not to building. Further research—with some aeronautical engineering help and Catia software courtesy of friends in Frank Gehry’s office — led to conversations with ship- builders from as far afield as Scotland and Korea. In the end, only a German company could roll steel to a width that, once trimmed and upended, could be used to produce a piece to walk into. The process, from initial studies to the exhibition opening, took four years.

In 2002, I was involved briefly with Serra’s work in my role as Caruso St John project architect for the Gagosian on Britannia Street. “The architecture is open and rectilinear, good light, but the staircase is clunky,” Serra says. Regular emails from the client would ask if it was possible to raise the height of the gallery spaces yet further. As Serra’s steel- workers invested in new rolling equipment, the size of the pieces they could produce was increasing — so naturally, the gallery should follow suit.

When I asked Serra whether he now considers the gallery to be part of the work, he assures me he always worked with found situations and this was not a direction he would be pursuing. None-the-less, a significant cost for the Gagosian was the 1,200sq m, 450mm-deep reinforced concrete slab designed to take the weight of his sculptures.

The Britannia Street building has three major display spaces and a fourth, smaller gallery. Four big steel sculptures have been installed in the three main spaces, and a set of four steel pressings are mounted on the wall in the smaller space. Across town at Gagosian’s Davies Street gallery are a series of Serra’s oil stick drawings. The two sites and five rooms present almost the entire range of Serra’s work except, as he pointed out to me, landscape.

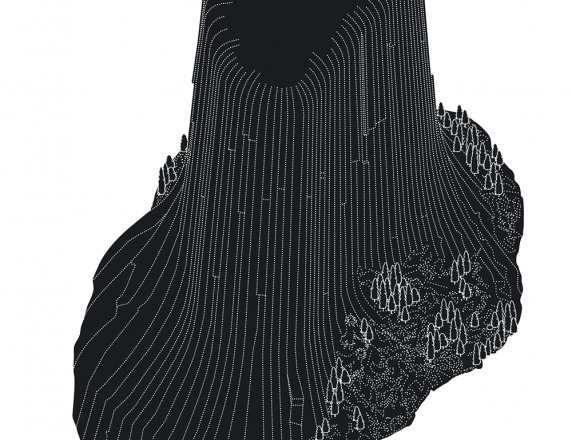

In the largest of Britannia Street’s spaces are two rust-red torqued ellipses, one the inversion of the other. These pieces are reminiscent of the original torqued ellipses and those on permanent display in the Guggenheim Bilbao. They defy easy description, just as they defy being imagined as a single image. What one can say is that they have a strong effect on your balance, peripheral vision, and sense of scale, orientation and time. This last is perhaps the least obvious but most significant effect of his work.

Resisting pigeonholing

Serra strongly resists any minimalist pigeonholing with the likes of Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt or Carl André. “I came up with a different generation— Robert Smithson, Karl Neumann, Eva Hesse, the down and dirty kids,” he says.

“The orthodoxy of minimalism was like a high priesthood: painting structure into the object, one plane in the gestalt of the all. You didn’t have to walk around the pieces to understand this excitement. It was given.”

Serra helped Robert Smithson build Spiral Jetty, and after his death completed Amarillo Ramp, both seminal works in the canon of land art. Minimalism’s fixation with the object was being pulled apart literally, with sculpture expanding into its contexts. To appreciate a Smithson or a Serra, you had to walk a round it, probably slowly, sometimes at an angle as the overhanging walls encroached on your private space.

This effect is brought to an extraordinary level of intensity in the piece in Britannia Street’s second gallery. A dark grey steel form hunkers down in the space, almost filling it completely. On entering one end, you are able to walk down a 700mm-wide passage with con- centric, curved leaning walls on both sides. This passage continues for what seems an eternity, doubling back on itself three times before it reverses orientation and leans in the other direction. At this moment, I was completely lost and quite unsure what to expect next.

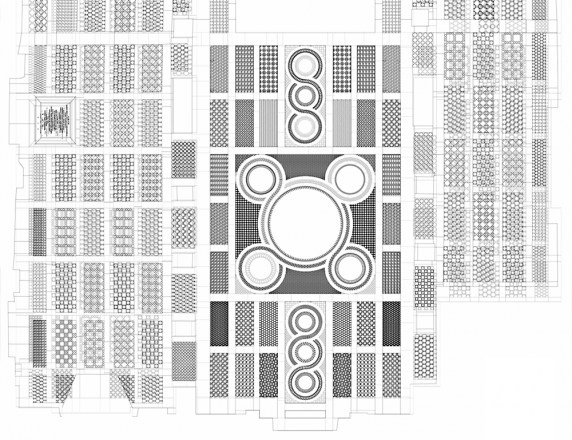

In recounting the experience in the interview, I found myself describing the Tardis and how it was used by Doctor Who for time travel. Serra, who had been drawing with a thick clutch pencil on large sheets of yellow paper throughout the interview, asked me to draw a plan of the sculpture. I tried, but as soon as I got to the change in direction, I couldn’t draw my way out of the knot I’d created. Serra chuckled and repeated: “I’m interested really in the evolution of form, induration, the body and movement through time. And not in image.”

So unlike other work that can fit on a plinth and be moved around, photographed and published, you really have to get inside these pieces to know them.